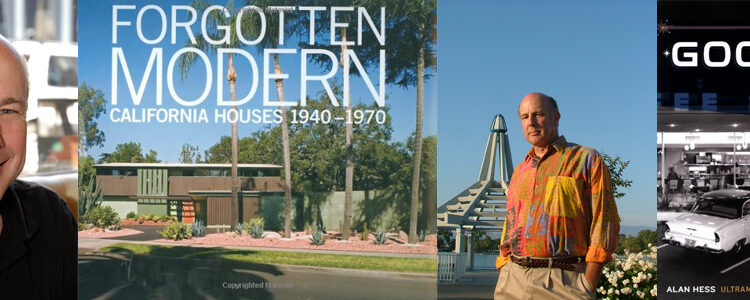

President's Award: Alan Hess

As an architect, architecture critic, historian, author, educator, and preservationist, Hess has elevated the roadside and commercial architecture of post-World War II to its rightful place in the canon of architectural history. He has done so by taking seriously the hidden, forgotten, neglected, and unsung places that helped define postwar living.

Coffee shops, ranch houses, suburbs, Palm Springs, Vegas, Irvine: Hess has applied scholarly principles to the underdogs of architecture, demonstrating why they are “as much a part of American culture as the Gothic campus, the Federal-style house, or the Beaux Arts civic center.”

Published in 1985, Hess’ first book, Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, celebrates its thirtieth anniversary this year.

This seminal work turned the then-derogatory term “Googie” on its head and fostered a newfound respect for one of Southern California’s signature styles.

Nineteen books and more than a hundred articles, essays, and lectures later, Hess is the preeminent authority on Modern architecture and urbanism in the mid-twentieth century. He writes about Frank Lloyd Wright, but also Edward Durell Stone, Stanley Meston, and other architects who don’t get the attention they deserve. He was writing about John Lautner, William Pereira, and Oscar Niemeyer before they were household names among architecture buffs.

He challenges us to rethink what’s worth preserving and why. “The examples are not obvious,” he wrote in 1995. “We must look for them carefully, even if they are beneath our noses, so much a part of the fabric of life that they are not noticed as significant. We must train ourselves to see beyond the boundaries of current taste…There is a hidden history that deserves and demands exploration.”

He also walks the talk. Far from purely academic, Hess’ work seeks to achieve the very real goal of preserving important places, regardless of their age, purpose, or reputation. Hess has worked actively to preserve important examples of postwar architecture, including the world’s oldest remaining McDonald’s in Downey (Stanley Meston, 1953), Pasadena’s former Stuart Pharmaceutical factory (Edward Durell Stone, 1958), and most recently, Norms La Cienega (Armet & Davis, 1957).

In 2013, marking the 60th birthday of the Downey McDonald’s, Hess wrote, “In 1983, the idea of a McDonald’s being a historic landmark was a punchline, even among architectural preservationists. How could a hamburger stand be historic, let alone significant? How could a suburban building be good architecture? How could [architect] Stanley Meston stand in the pantheon of architects with Mies van der Rohe?

How? It's a design that’s inseparable from its time, place and people. That’s what really good architecture is.”