Place

Freehand Los Angeles

A long-neglected former office building was transformed into a vibrant hotel, connecting people to their past and each other.

Place Details

Address

Get directions

Architect

Year

Style

Decade

Property Type

Community

Freehand Los Angeles, a boutique hotel with a rich history, stands on the corner of Olive and Eighth Streets in downtown Los Angeles.

Built in 1924, the Renaissance Revival-style Commercial Exchange Building was designed by architects Walker & Eisen. The Los Angeles Times once described it as one of the most “substantial, utile, and handsome [buildings] that talent and money could produce.”

The coveted office building was the first in the area built to the maximum height limits of the time. It had three high-speed elevators and much-desired two-hour street parking nearby. It housed the headquarters for the Owl Drug Company, as well as offices for dentists and Tarzan author, Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Just three years after opening, the building faced demolition when a City ordinance called for the widening of Olive Street in order to alleviate traffic congestion. Self-taught contractor George Kress came up with an unconventional solution: remove a five-foot-wide portion from the center of the building, and push the two remaining halves together.

In 1935, seventy-five men closed the gap in nine hours at a cost of $60,000. Astonishingly, the move did not disturb any tenants or break a single window. The only visible evidence of the move is a single-window bay on the Eighth Street façade.

The Commercial Exchange Building thrived through the 1950s, but suffered from incompatible alterations in the ensuing decades. Terra cotta surrounding the main entrance was removed and covered with red granite. Laminate paneling covered marble walls, vinyl covered original flooring, and acoustic tile hid the building’s vaulted coffered ceiling.

The building eventually fell into disrepair and stood largely vacant, except for squatters and vandals. When the current owners purchased the property in 2014, the property was in shambles. Bullet holes littered the windows, graffiti covered the walls, and the interior contained trash and biological waste.

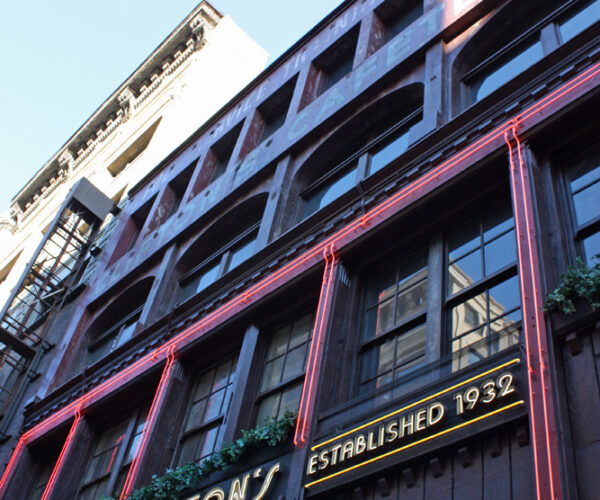

The project team uncovered a host of long-hidden features, including the original wooden transom and at least one storefront dating from the 1930s. They meticulously removed decades of old paint and incompatible flooring, revealing an original Owl Drug Company tile mosaic, now visible in the dining room. They reconstructed missing pieces based on remnants and photographs, and they restored the original neon blade sign.

Due to the lack of structural drawings, the project required a significant amount of redesign. The building’s narrow footprint—not to mention the removal of five feet in the 1930s—made structural upgrades particularly challenging.

Today, the building welcomes locals and travelers as Freehand Los Angeles. The owners used an owl motif, from room keys to stationery, in a nod to the building’s past.

The owner initiated the building’s 2017 designation as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Landmark. The project benefited from Federal Historic Tax Credits, which narrowly survived the 2017 tax overhaul.

Freehand Los Angeles exemplifies how historic buildings can live on through new uses, connecting people to their past and each other. This project earned a Conservancy Preservation Award in 2018.